From Chapter 1:

The Day Everything Changed

When someone you love ages, you don’t often notice the incremental changes the years bring. Watching

him

walk up the hill that morning, my only thought was, “Here comes Chuck.” And I smiled in

anticipation of what he would say when he joined me. It was all magnificently normal.

Until I noticed that he was shuffling through the gravel as if his canvas shoes were filled with cement.

Read more

My smile faded. He’s kidding around, I thought. He never walks like that. But as I watched him

struggle, I felt heat rise up my neck and flood into my cheeks. When he reached the picnic table, he

threw

himself onto the bench opposite me.

“Why am I having so much trouble walking? I must really be getting old.”

Then the right side of his mouth drooped, his eyes rolled, and he leaned back precariously. As I rushed

over

to steady him, he muttered words I couldn’t understand.

I looked in the direction of the dock, hoping to spot Isabel and Lillie. But they were nowhere in sight.

Lillie was a nurse, and I wanted her opinion. Should I wait? After a few seconds, I took out my cell

phone

and dialed.

“9-1-1. What is your emergency?”

“I think my husband is having a stroke.”

From Chapter 17:

Go Inward, into Your Proper Darkness

Let go of the past.

When Chuck taught Julius Caesar to his high school students in Chicago, he would challenge them to cite

three

consecutive words from the play, and then he would identify the act and scene from which the words came,

the

character who spoke them, and to whom. A few weeks ago when we were filling out our absentee ballots,

Chuck

began to weep because he could not remember his last name.

Read more

Say hello to a new chapter of your life.

Professor Williams wrote these words about Samhain [Irish New Year]: “The past is gone and can

never

be revisited. The future, no matter how daunting it seems, lies ahead and should be approached with a

child’s innocent bewilderment, asking: What do I need to learn in this new chapter of my life?

What do

I have to offer? What do I fear? Why do I fear it? What can I learn from my fear? How can I go forward

with

strength and courage and wisdom? How can I love others and myself more completely?”

Her questions overwhelmed me, yet I was quietly confident that with patience and time, answers would

come.

I thought about the bulbs we had planted, now lying deep in the earth. They would lie dormant throughout

the

winter. In the spring, their offshoots would tunnel through the black dirt, and then purple, yellow, and

white blossoms would emerge into the sunlight. I wondered if I could ever mirror that process. At this

point,

when it took everything I had just to get through the day, I could identify with the bulbs buried in the

darkness—but not with the spring flowers. However, our Samhain celebration reminded me to be patient.

From Chapter 23:

Blue Clothes

Chuck also experienced delusions, some of which were elaborate. One day in January 2004, I entered Room 30

and

found him working on a children’s jigsaw puzzle. Although he was still in his pajamas at 2:00 p.m.,

he looked very normal that day—legs crossed, holding a puzzle piece in his hand while studying the pieces

on

the card table. Classical music played on his radio. I sat down and noticed a pile of clothes next to his

wardrobe.

“Why are those clothes on the floor?” I asked.

Read more

He looked at me as though I had failed to grasp the simplest concept. “They’re blue.”

He

returned his attention to the puzzle.

I turned up my hearing aids. “They’re what?”

“They’re blue!” he repeated more loudly.

“So . . . what’s wrong with blue clothes?”

He spoke with exasperation. “You can’t wear blue if you’re in the Nazi Army!”

“But you’re not in the Nazi Army.”

“Do you mean to tell me this place is not owned by the Nazi Army?”

“As far as I know, it’s owned by a corporation in Milwaukee.”

He looked abashed, but he accepted my explanation. “I suppose those will have to be

washed,”

he said, looking balefully at the pile. “Since they’ve been sitting on the floor.”

From Chapter 24:

Viaje Bien

One dark morning in March, I boarded a Seattle Metro bus feeling terribly depressed. I walked down the

mud-streaked aisle and slumped into a rear seat, hoping no one would sit next to me. The bus reeked of wet

wool and mothballs. A noisy heater blasted hot air across my legs, and raindrops slid down the window.

Read more

I stared blankly at the bus’s overhead signs honoring the Metro Employee of the Year and the Metro

Mechanic of the Year. Next to them was a sign titled “Ride right” that explained how to be a

good bus rider by not bothering others and having the correct change. Its grammar bothered me. The

Spanish version was better: “Viaje bien.” Ride well.

But I was not riding well that day. Not even close.

I knew where I was going and what I would do when I got there: I was scheduled to record a radio show at

the library for the blind. But I felt completely without purpose, energy, or even a shred of

understanding about why that might be important or why I was going through these familiar motions.

Chuck wasn’t going to get better, and at that moment I wasn’t sure I was either. I

didn’t understand what I was supposed to do in this brave new world. As his wife, I think I was

supposed to take care of him. But apparently, I’d failed at that.

From Chapter 25:

The Public Is Not Allowed in Linen Closets

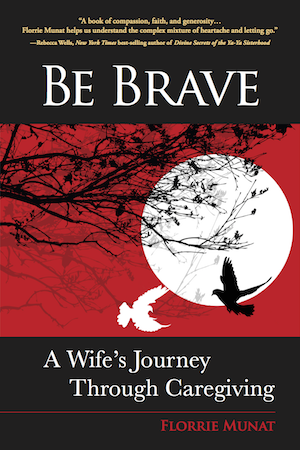

Chuck continued to be brave even while living in the clamp of dementia. He got up every morning, did the

best he could, and didn’t complain. I wanted to be brave like him. But in my life as a caregiver, my

way of being brave had to be different.

For me, being brave began with waking each morning to an empty space next to me in bed and getting up

without rupturing my heart.

Read more

My brand of bravery meant walking through the front door of St. Thomas Health & Rehabilitation

Center

every afternoon, unsure of what challenges were waiting for me. Being brave meant continuing to love my

husband despite his alarming transition from the patient man I had married to a man who sometimes acted

unreasonably or incomprehensibly.

As you can guess, things didn’t always go smoothly. There were many days when I was not brave.

I cried. I despaired. I wanted out. But I kept my feet moving. Being brave did not mean being unafraid.

Being brave meant getting up each day in spite of being afraid. What choice did I have?

From Chapter 32:

What It’s Like Inside My Brain

Chuck gave me an obvious clue about his condition on the day Sharky was born, but once again I missed it.

On June 30, 2002, Chuck and I stayed in a hotel in Olympia so we could be present at Lillie’s

Caesarean section, scheduled for 7:00 a.m. the next day. Chuck didn’t sleep all night and was

exhausted in the morning. So I drove to the hospital alone to attend Sharky’s birth.

Read more

Around 11:00, Chuck phoned and asked me to pick him up. I did, and we had a celebratory gathering in

Lillie’s hospital room. Then Chuck asked me to drive him back to the hotel so he could take a nap.

Tired of all the back-and-forth trips, I said, “Why don’t you drive yourself?”

He looked at me as if I’d asked him to pilot the Space Shuttle. “ I don’t know where

the hotel is.”

I drew him a map, showing the right turn at the bottom of the hospital driveway, the straight shot into

Olympia, and the right turn onto our hotel’s street. I walked him outside because he

couldn’t

remember where the car was parked. Clutching the map, the former Chicago cab driver hesitantly climbed

behind the wheel. He said, “You may never see me again.”

I thought he was kidding. “C’mon, it’s not rocket science!”

As he put the van into gear, he glanced at me and muttered, “You don’t know what it’s

like inside my brain.”

From Chapter 39:

The Ides of March

During his time at St. Thomas, I had come to love the “new Chuck,” who was simply a different

manifestation of the “old Chuck.” They were interwoven parts of the same man, and I loved the

Chuck who sat before me in his

wheelchair as much as the one who had stood beside me at the Connecticut waterfall the day we promised to

be husband and wife “for as long as our love shall last.” Well, it had lasted a good long

time: forty-one years.

Read more

Although our lives had become ensnarled in the tentacles of Lewy body dementia, even illness could not

take away what we’d always had: an abiding love and respect for each other. And that kind of love

does not come to an end.

When my caregiving saga began, I realized that one day we might be faced with the question, “What

makes existence meaningful enough to keep on living?” That question came into clear focus one

night at St. Thomas Health &

Rehabilitation Center. It was March 15, 2009. Beware the Ides of March.

Excerpts from the Book